Private API Credits: A Simple Construction

Introduction

Privacy is back on the public radar. Over the past year, multiple prominent players within the Ethereum ecosystem have been unveiling their privacy roadmaps. More recently, the Privacy & Scaling Explorations (PSE) team have undergone a metamorphosis: they are now the Privacy Stewards of Ethereum. The price of Zcash increased 9-fold over the last year, and shielding protocols like Railgun have continued growing in deposited liquidity. Despite this rapid growth and renewed attention, a recent report by PSE shows that overall adoption remains low, with many pain points persisting for more privacy conscious users.

One concern of the report stood out to us in particular: a user setting up Privacy Pools locally was confused that they had to configure an Alchemy API key to get the front-end running locally.

There are so many leaks if I’m using Alchemy… what is the point?

They have a point. An API key is linked to an account on a certain platform, which contains personally identifiable information (PII). It also surfaces the full chain of requests made by that single account. Having an account is clearly needed for purchasing API credits, as well as potentially any compliance checks. But is the link between an API key and the PII really necessary? Additionally, do we really need a persistent identifier across all requests? Can it be avoided so users can remain safe from honest-but-curious providers or data breaches? To answer this question, we’ll need to take a detour and look at a fairly annoying but ubiquitous aspect of browsing the internet: CAPTCHAs.

CAPTCHAs & Privacy Pass

CAPTCHAs were introduced to identify requests coming from humans instead of bots, and are used in website protection services like Cloudflare. This was a necessary service to protect websites from DoS attacks, but it introduced a lot of friction for users. Millions of collective hours were wasted in solving semi-useless puzzles as a proxy for personhood.

When Privacy Pass was introduced in 2017, Cloudflare was one of its first adopters. Why? Because Privacy Pass provided a way to drastically reduce the amount of CAPTCHAs users had to solve online, all while maintaining user privacy. This last part is important. Cloudflare could technically issue a persistent identifier to users solving a CAPTCHA, that can be redeemed every time a user is presented another challenge. But that would allow Cloudflare to trivially track the complete browsing history of a user. Not great.

The Privacy Pass protocol solves this by leveraging smart cryptography. Instead of a persistent identifier, successful solvers of a CAPTCHA get a set of blinded tokens that are signed by Cloudflare. The magic happens when the user receives these signed, blinded tokens: they can unblind them into a form that is cryptographically unlinkable to the original blinded token, all while the cryptographic signature representing the stamp of approval remains valid! These unblinded tokens are what the user (the Privacy Pass extension to be exact) redeems when they are presented with a challenge, and Cloudflare allows them to bypass the challenge because they see their valid signature on it. To Cloudflare, every token looks completely random, so they can’t track users with this mechanism.

Privacy Pass for General Authentication

In the Privacy Pass Architecture RFC, the issuance of tokens happens after a process they call attestation. In this context, an attestation just signifies the fact that you have satisfied the attester. But an attestation can be anything: with CAPTCHAs, your attestation is that you solved a puzzle correctly. With Apple’s Private Access Tokens (their extension of Privacy Pass), what’s being attested to is the fact that the user is using an Apple device, is logged in to an Apple ID, and is not rate limited. Aside from the lock-in concerns, this is neat because it’s all private.

If we generalize the Privacy Pass mechanism, it can be used for any form of private authentication, not just CAPTCHA puzzles. The magical property here is the unlinkability between the issuance of tokens, which happens after a successful attestation, and redeeming those tokens. This mechanism is a powerful and private alternative to persistent session identifiers.

Kagi, a subscription-based search engine, realized this as well. They use Privacy Pass for exactly this mechanism: allowing authenticated users to execute private, unlinkable searches.

An astute reader may have realized where we’re going with this: this protocol could easily be adapted to retrofit RPC providers with private RPC requests. It could completely sever the link between signing up and buying credits, and then spending those credits in subsequent requests. RPC providers can still work with their prepaid API credits model, they just won’t be able to correlate any of the requests with the original accounts, or track a single user over time. This would (almost) solve the problem our user was having! We can even design it in a way that users of client libraries barely have to change anything in their workflows, but more on that later.

Key takeaway: the same mechanism that replaces repeated CAPTCHAs can replace persistent API keys.

The Protocol

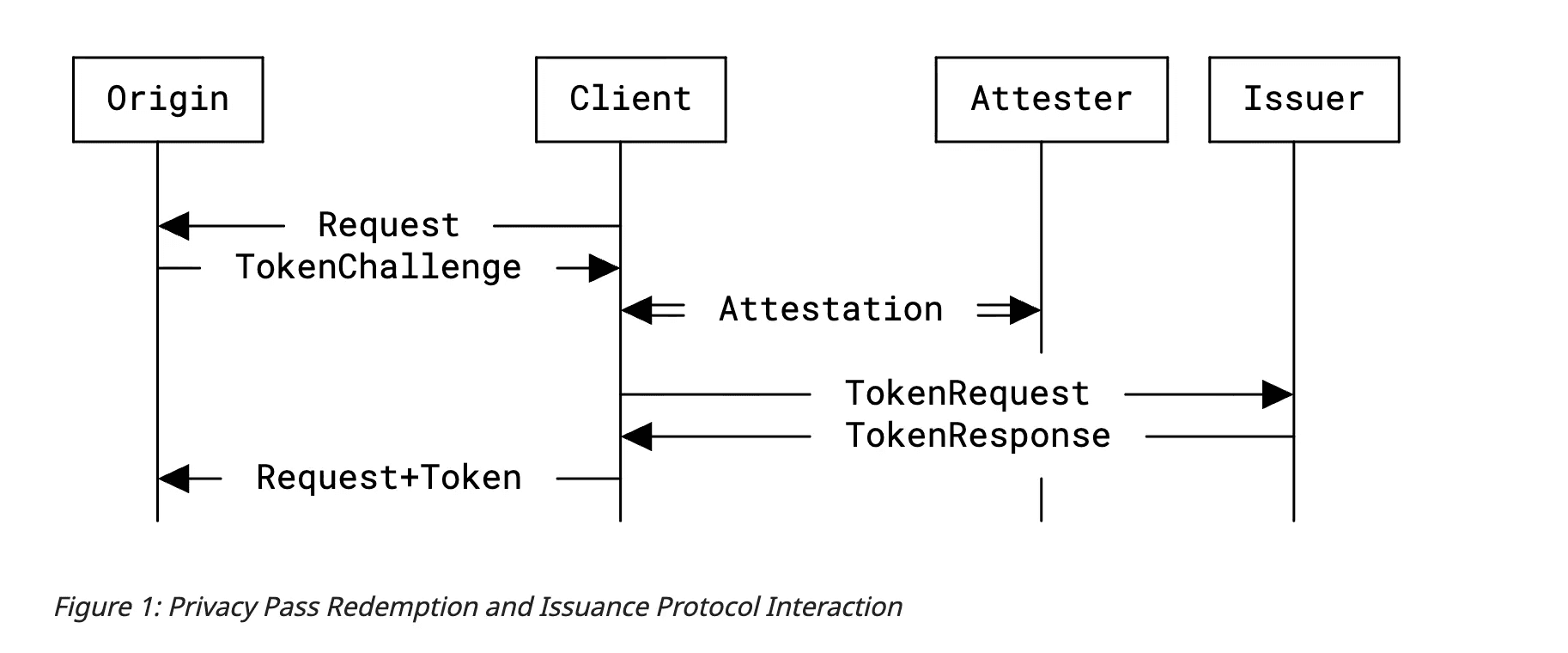

So how does Privacy Pass work? We won’t get into the actual cryptography here, but rather give you a high level overview of the interactions to help you build an intuition. The first iteration of Privacy Pass based on blind signatures is the easiest to understand, so we’ll start there.

Blind signatures are usually conceptually explained with carbon paper. Imagine a voting center where a local community goes to vote. Before shipping off the ballots to a central area where the votes are counted, the local voting center certifier is required to sign (certify) each ballot. Certifying in this case consists of ensuring that the ballot came from a person that was present, and that it’s their only ballot (no double voting). The problem is that voters are not comfortable sharing their ballots with the certifier, because they don’t trust him not to look at the vote while signing.

Someone comes up with a system to address this:

- Put a piece of carbon paper on top of the ballot, wrap it in an envelope, and seal the envelope.

- Give the envelope to the certifier who will authenticate you and then sign the envelope. Because of the carbon paper, the signature will be transferred onto the ballot.

- When votes are tallied, the counter can unseal the envelope and find the certifier’s signature on the ballot, thereby knowing the vote was valid.

This system ensures that the certifier can authenticate a ballot without seeing the actual votes, and the content of the ballot can then be verified by a different party who doesn’t know the voter!

Blind RSA Signatures

In the digital realm, this system can be replicated with cryptographic primitives like RSA blind signatures. In the issuance process, clients can generate a bunch of random nonces , and then blind them with a blinding factor . The blinding process works such that any signature on the blinded nonce will also be valid on the unblinded nonce, but the signer cannot recover the unblinded nonce because it doesn’t know what is.

In practice, Privacy Pass has moved toward VOPRF-based constructions, but blind RSA is easier to explain and shares many of the same properties.

We’ve skipped over some details of RSA blind signing here, but this should give you a bit of an intuition of how it works.

Architecture

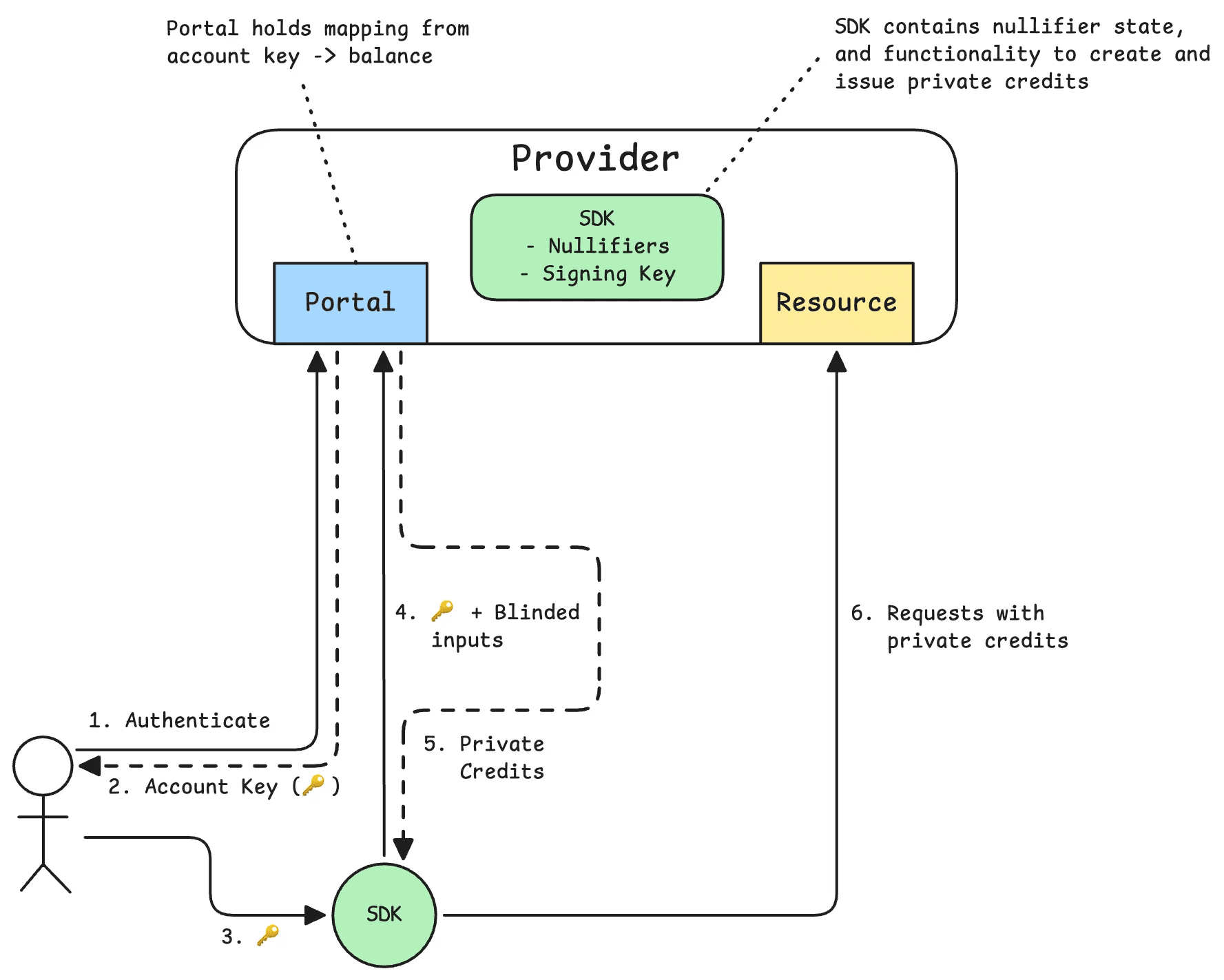

As a thought exercise, what could a UX-friendly private API credits architecture look like? Let’s define the components first:

- Provider: hosts a portal for users to sign up and purchase credits, and hosts protected resources that users want to access privately. In the case of RPC providers, the resources would be the nodes they host, accessible over JSON-RPC.

- User: user of the system, signs up for an account and purchases credits through a portal. Interacts with the resources through a client.

- Client: software operated by the user that interacts with the provider and its resources, and abstracts away the complexities of dealing with private credits.

The logic of both the Provider and the Client will have to be modified to replace regular API keys with private credits. However, for ease of use, we can still use a key that uniquely identifies a user, and allows the client to programmatically request private credits from the provider, and the provider to keep track of balances. This is not a problem, because all this information is contained to the initial authentication and issuance context. This key will not be used when making actual API requests. We’ll call this key the Account Key.

Client

We’ll start with the client. One of our goals here is to minimize the friction introduced by private credits. Therefore, the client should encapsulate all of the following logic:

- Producing random nonces and blinding them

- Interacting with the provider to receive blinded, private API credits

- Attaching those credits to RPC requests to authenticate them

As mentioned before, we can make use of the account key. This is a key that uniquely identifies the user and has an associated balance that it can mint in private API credits. All the user has to do is purchase credits on the portal and instantiate the client library with the account key. It will take care of the rest.

Provider

We can explain the functionality that would need to be added to the provider in the form of a hypothetical Private Credits SDK. This SDK would be initialized with a keypair (the Issuance Key) of which the public key is known to all clients. The corresponding private key will be used to sign private credits with.

The portal would manage user billing and account keys, and upon issuance it will use the SDK to blind sign credits.

One key requirement of the SDK is that it should contain some nullifier set of already spent credits to prevent double-spending. This means that on credit redemption, the unblinded nonces provided with API requests should be added to a cache to indicate that they’ve been spent.

Practical Considerations

Nullifier State

Edge services need to redeem and validate private credits, which includes invalidation by adding the nonce to a nullifier set. To limit state growth, the first requirement is the use of epochs. These are fixed intervals of time that set bounds on the validity of a private credit (i.e., they expire after 1 epoch). This alleviates the state growth problem by being able to purge the nullifier set after every epoch.

Data Structure

The second consideration is that of which data structure to use, which can also have a big impact on state growth. We outline 2 options here:

- Small but probabilistic

- Large but deterministic

The first option contains data structures like Bloom filters that are extremely space-efficient. They can be used for membership testing just like a hash set, but they can render occasional false positives. In this case, this could mean that a certain credit could be wrongly marked as spent! Fortunately, because epochs limit the amount of possible items in a filter, it’s possible to configure the size of the Bloom filter to make these events sufficiently rare. Alternatively, newer constructions like cascading Bloom filters could be used as well.

The second option uses sets. These are deterministic (no false positives), but grow linearly with the number of elements in the set, and are thus not very space-efficient.

To Share Or Not To Share?

In a highly-available setup, many API endpoints may exist to service requests. This means that each of them should have access to the latest nullifier set. Sharing this state directly between services with strong consistency is not an option, because it would require consensus between potentially distributed services.

What we would recommend instead is to have a dedicated service for redeeming credits that manages the nullifier state. One could make this highly available, but probably only within a region to ensure low latency.

Compute Units Accounting

Since RPC providers use compute units for accounting, private credits should be denominated in CUs. For example, 1 credit could represent 10 CUs. This works for all models where the cost is known upfront. However, more research is needed to make this work for models with dynamic API costs, like LLM APIs with token accounting.

Latency

Modern Rust-based privacy pass libraries like the one used in the Brave Browser are quite fast (link). Signing a batch of 30 tokens takes ~1.2ms, while redeeming 30 tokens takes ~850µs. Check out the benchmark here: https://github.com/brave-intl/challenge-bypass-ristretto/pull/77.

Interacting with the nullifier service is also in the hot-path, so should be accounted for as well.

Improvements

The Privacy Pass Architecture RFC defined 3 logical roles: the Issuer, Attester, and Origin. In the previously discussed design, all of these roles were played by the Provider. The portal authenticates users and verifies balances (attestation), and then issues credits (issuance). The resources here are also exposed by the provider (origin). The RFC actually mentions that there could be cases where this presents a risk.

All of these risks boil down to the simple observation that privacy loves company. If your anonymity set is small, because this feature is exposed as a separate paid plan that initially does not have a lot of users, you have a chicken-and-egg problem on your hands. With only a small set of users, the anonymity guarantees are quite low. But this would be mitigated as soon as there are more users using the feature, and the more users, the stronger the privacy guarantees. On the other hand, if this feature is introduced as a default, the problem would not exist.

Another risk the RFC mentions is the following:

Origin-Client, Issuer-Client, and Attester-Origin unlinkability requires that issuance and redemption events be separated over time […], or that they be separated over space, such as through the use of an anonymizing service when connecting to the Origin.

Separation over time is useful because of timing correlation analysis: if a user gets issued credits, and immediately after that starts redeeming them, it could be possible to correlate the 2 events. Note that this is once again tied to the size of the anonymity set: if there are many users, that are constantly issuing and redeeming, this analysis becomes sufficiently hard. But to be safe, the client should implement this separation in time.

Separation in space is related to network metadata: if the same IP is used in the issuance process, and later on when redeeming credits, unlinkability is also lost. It is therefore necessary to anonymize either of the 2 interactions through a third-party service. Another IETF standard that could be leveraged here is Oblivious HTTP (RFC 9458). Oblivious HTTP introduces third-party relay in the request path that hides network metadata from the origin, while not being able to deduce anything about the request itself other than its source and destination. From a trust perspective, it’s similar to iCloud Private Relay: it works unless the 2 parties collude.

Use Cases

We’ve explored private API credits from the perspective of private RPC requests. As mentioned before though, the construction is general enough to work in any deployment that uses API keys for authentication. It is especially relevant in scenario’s where decoupling account information (PII), with API usage is desirable. One particularly interesting case is private LLM provider APIs.

With private credits, prompts and conversations will be unlinkable to PII (unless you include PII in the prompts). We think that this should be an option that LLM users have if they don’t want the providers to be able to construct a complete picture around their identity. There are some interesting open problems here though:

- Conversations are by their nature a chain of messages, so achieving unlinkability between requests is not really possible. Maybe this is less of an issue as long as it can’t all be linked back to a certain identity.

- The exact cost of an API call in tokens is not possible to know in advance, so a variant of this that works with dynamic costs should be investigated.

Conclusion

All of the primitives for replacing the API key with private credits are there, and on top of that, they are standardized by the IETF. Multiple companies have open-source, audited implementations of the cryptography. In conclusion, all of the building blocks exist, and are waiting to be put together. If you are interested in collaborating with us on this, please reach out to dev@chainbound.io or ping @mempirate on X.